Appalachia By Train And Raft

The Amtrak Cardinal and Capitol Limited lines travel from Chicago to the east coast nearly every day, allowing access to a number of popular, runnable rivers. With a packraft, reaching them is an easy matter of packing up my river gear, riding on a train, and hiking out to a boat launch. On this tour, I combined three different Appalachian river trips into a week-long itinerary of train rides, paddling, and hiking.

Day 1: Packrafting the Potomac

I leave the train at midday and find the riverside trail going west. The river rapids of the Potomac echo through the trees. The afternoon sun is hot and my pack is heavy. I walk for two miles and reach a boat ramp owned by a local tubing outfitter. The guy tells me to stay away from river right. It has collected a lot of debris from flooding and one section of it is sieved out. The reality of this advice, and the collective roar of swiftwater a thousand feet downriver is making me nervous. I’m scared of it. But I can’t look away.

I’m back in Harpers Ferry for the fifth time, setting up to run my packraft on the Potomac River past the town to the 340 takeout downstream. It is a popular Class I-II section of intermittent ledge rapids, drawing a lot of open top kayaks, canoes, duckie boats, innertubes, and every so often some dude with his own green inflatable boat and GoPro that he rigged off of the stern.

I launch out and paddle to the left side, looking for a runnable line through the rocks. Little channels pour every different way and I’m forced to navigate on the spot. I recall seeing a straight current to the right in the satellite view. But since that section isn’t safe, I have to paddle through a boulder garden, often ferrying along ledges to find a way through. My camera keeps going out of position when I go over a wave, because there’s no way to fully tighten the ball joint on my tripod. So I keep having to fix the camera position, which is the most important thing about this trip, because I’m all in it for the Likes.

I paddle fun, bumpy rapids for a quarter mile, then pass the town and the confluence with the Shenandoah. The river widens. I hear another rapid ahead. Again, left is the way through. As I go east, the clouds behind block out the sun and the valley darkens. I need to hurry.

The river channels into Whitehorse Rapid, the only wave train of any notable size. Even so, you could run it in an innertube, fall out, and float harmlessly to the end. I skirt the right edge, ferry to the boat ramp, pack up, and scramble up to the 340 bridge. The hostel sits on a bluff on the other side. It’s my fifth time staying there.

I usually travel alone because I like to do everything on my own terms, but the more extroverted part of me likes to meet people when I do. Which is why I like hostels. They bring adventurous people together in an environment that allows travelers to connect with each other, while at the same time continue on with whatever their thing is. The one in Harpers Ferry is particularly interesting because it hosts a lot AT thru-hikers, cyclists on the C&O, people on roadtrips, and guys like me coming out and doing random shit.

This time I meet a group of 25 people from DC on a cycling meetup. They rode out here on the trails, plan to hike Maryland Heights and go tubing tomorrow, then ride back the day after. When I meet them, I realize this is a demographic of people here that I had never considered: Weekend warriors from DC.

I have beers and shots with them as we trade travel stories and river trips. One girl is bringing her kayak to Gauley Fest in two weeks. Another one has questions about Iceland. And another one is a government security employee who wants to get out of it and travel more. So do I. If it were up to me, I would be traveling, taking pictures, making videos, and writing stories every day. But vacations will have to do for now. I finish one more beer with them at a bonfire and go inside to my dorm.

Day 2: Capitol City Layover

I hike back to the town and board the eastbound train in the late morning. Even with my ultralight gear – packraft included – I feel like my pack is weighing me down. I have to get rid of this thing if I’m going to find a brewery. When I get to DC, I check it in with the agent and go outside. Without it, I can walk around instead of hike, if that makes sense.

I load up Google Maps and put in “Brewery”. Twenty minutes later, I’m at Capitol Ale House sitting in front of a colorful flight. Vanessa is texting me something funny. We talk a lot, even though she is in Sweden and I’m in the states. I met her on a trip last year and we have been talking about Sigur Ros over WhatsApp ever since. I send her a link to a B-side from Julianna Barwick, whose angelic voice can melt a heart of stone.

I leave Union Station on the Crescent train for my hometown.

Day 3: The Shenandoah by Packraft

I drive north and park my parents’ van at the Inskeep launch three hours later than I meant to. It takes me 45 minutes to set up the raft and sort my gear. I get moving on the river at 10, losing most of the good hours of the morning. The Shenandoah is mostly calm, opaque and brown from rainstorms washing dirt from the mountain streams. It’s low but has one or two good feet above most of the ledges, often enough for me to get through without looking for a line.

Halfway through the day, I start passing large groups of tubers and kayakers. Why didn’t I think of this in college? I lived in Harrisonburg for years and it never occurred to me that a crew of us could float this river. Complete with outfitters and coolers of beer, we could have been 20 strong. But the truth is, there is a lot of natural beauty in the Blue Ridge Mountains and West Virginia that I took for granted back then. Hell, the AT is 12 miles away from the farm. But that’s why I keep coming back now. I’m making up for lost time.

The day gets hot and I’m running out of energy. It’s my own fault I didn’t start earlier. I have to get focused, because I need to scout the Compton Rapid, considered locally as the boogie rapid of the river. I climb through bramble to get to the riverside and take a look. I can see the line clear as day. You start it on center right to miss a ledge hole on the left, and then work your way left to avoid another one on the bottom right. I easily run it to the bottom.

I take out at Mile 19 and dry my gear in the sun. It’s late in the day and I’m exhausted. I hike the Indian Grave Trail a few miles up the ridgeside and find a flat area to set up camp.

Day 4: The Most Convenient Shuttle Ever

I pack up and keep going up the ridge. To my right I discover a spring and refill my bottles. The trail steepens as the 9am sun shines between the trees, already hot in the morning haze. In its steepest part, this trail is like a staircase of rocks cutting into the mountainside. The sun beats on my face and arms. I see the Shenandoah meandering below the humid backdrop of the Blue Ridge.

I reach the ridgeline of Massanutten Mountain and turn south. On a map you can see it circle around Fort Valley to the west, a small, solitary valley a few miles wide. One road goes through it from 675 to the valley’s end, 20 miles north. Even after all these years it’s the first time I’ve actually seen it.

I go south as the sun rises to an unforgiving angle. There are a lot of exposed rocky areas on the trail that offer little shade. When I do find it, I often stop to catch my breath and bring down my core temperature. I’m supposed to hike 11 miles to the trailhead, but with three full bottles and nowhere to refill on the ridge, I’m starting to have serious doubts if I can ration enough water for this.

What I do know is that Habron Gap is 4 miles from Indian Grave where I started. If it gets too hot, I’ll hike back to the road from there. I spend two hours fighting my way over ridgetops, and eventually get on a steady decline to the gap.

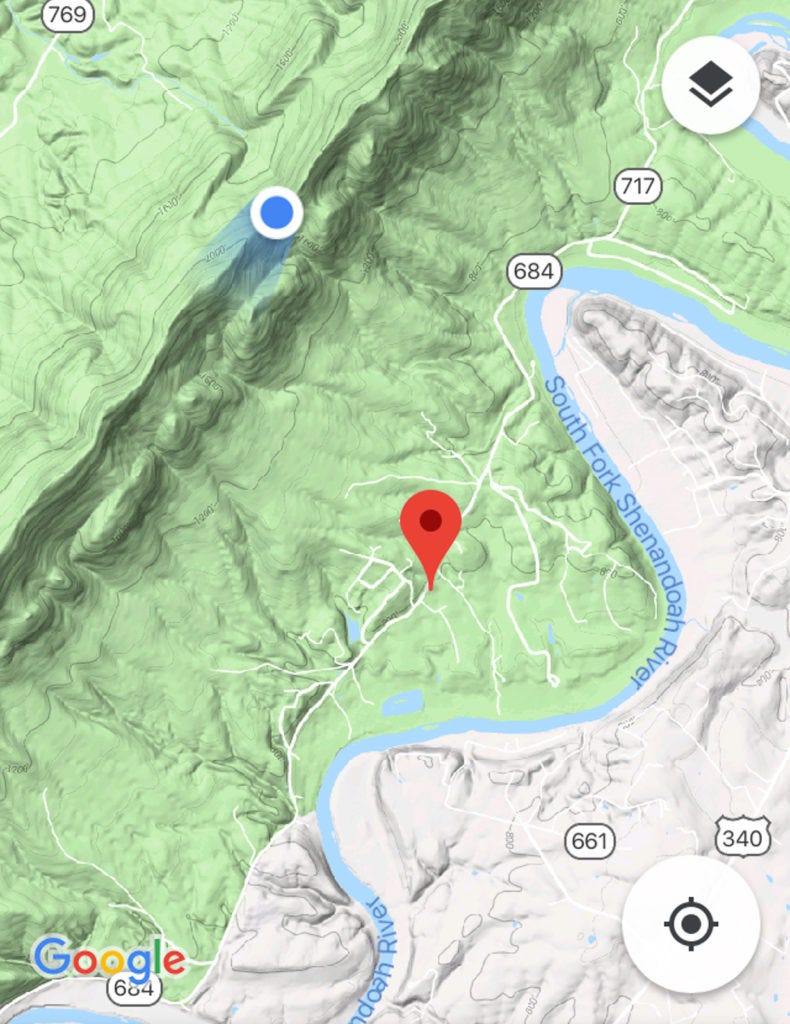

When I reach it, I have to decide. I can ration what I have left for seven more miles to 675, or I can hike down the ridge from here. I realize that even if I do have enough water, I would still be miserable in this heat. I take out my phone and look at the terrain map. Shenandoah River Outfitters is three miles down the mountain. I have to get from the blue dot to the red pin.

I finish my second bottle and start down the Habron Gap Trail. It’s smoother than Indian Grave, with less bramble growing along the sides. It goes steeply down the high ridge for a mile before leveling out in the trees. There, it flattens and I pick up my speed. It’s good to be in woods again.

Fifty yards to my right I hear the rush of a mountain creek. I go over, drink my last bottle, fill up all three, drop tablets into each, and keep going.

Finally, I make it to the road. I hike one last shitty mile to the outfitter and ask the lady where I can refill my water. She says there is a hose around the side of the building.

“Okay. What would you charge to shuttle me back to the Inskeep launch?”

“$30.” DONE. Twenty minutes and two Powerade bottles later, I’m loading up the van and driving out.

Several years ago, I stopped at the Thunderbird Café after another river trip, solely because of the name. I go there again, feeling like this might become a tradition. When I sit at the counter, I drink an extra glass of water. Just because I can.

Day 5: Hometown

The Shenandoah Valley is home. And it doesn’t matter how much time I spend away from it or how much I change, it will always be home. Though I’m too restless to ever move back here, I generally feel like I need to come back about once or twice a year to the quiet town – for the familiar hills, the fireflies, the sunrise on the Blue Ridge, and the sunset over Betsy Bell. Even the Walmart is part of my old life.

I borrow the van and visit my college friend Pete for coffee. We meet up nearly every time I come back. He and Jill had just recently lost their dog of many years and adopted a new puppy in her stead. As somebody who grew up around dogs for half of my life, I get all too well the grief of their loss, and how the joy of a new puppy can heal a family of that sadness.

Later, my dad drops me off at the Staunton train depot, where I once again leave my childhood home for a westbound adventure.

Day 6: Packrafting the Greenbrier

The river is six miles away. I plan to head out of White Sulphur Springs at 4am, determined not to make the same mistakes as before. But first, I eat a fruit breakfast my AirBnB host had prepared for me, and cut slices of the best artisanal cheese bread in the universe.

I hike out on the street in the dark, passing by the entrance to the Greenbrier, a huge world-class resort on the western edge of town, complete with a golf course, casino, spa, lavish weddings, expensive rooms, obscenely rich people, and the one thing I actually am interested in seeing: A decommissioned fallout bunker. The Greenbrier offers tours to their guests and the public to view the resort’s Cold War era fallout shelter, built to protect over 1,100 government officials from a nuclear disaster.

Maybe next time. I would need an extra day and I’m on a schedule. I walk by a parking lot and sit on a rock wall to rest. A security guard is just finishing his graveyard shift and offers me a ride. I load my backpack in his truck and get in the cab. He drops me off close to the interstate exit, a mile from the Caldwell boat ramp. I’ll take it. I get there and start setting up my raft at daybreak, which is the point. But first, I eat the artisanal cheese bread for breakfast. It is everything you ever want bread to be and more.

A canopy of fog hangs over the Greenbrier River and small patches of mist linger above the glassy flatwater. I push out and float into a smooth current. For six miles, I paddle through easy, bumpy Class I sections and the morning brightens. This is a scenic “family float” section of the river from what I can tell. I, however, do not waste my time floating anything, but make a hard pace in the cool morning.

The mid-morning sun breaks through fog and I pass the bridge at Ronconverte. A young fawn stares at me curiously from the river’s edge, perhaps the only eventful thing that happens before the valley narrows into a canyon. We stare at each other as I float by, careful not to spook it off.

The river bends sharply several times below the canyon’s cliffsides, passing from rapids to deep, clear flatwater pools. I think about why I do these kinds of trips. How the energy of a river really does amplify the beauty of a landscape. When it’s calm, it brings out the peacefulness of the countryside in a way that never quite happens on foot. And when it’s fast and wild, it crashes and rages in an echoing roar across the valley. I never feel truly alive like I do when I’m fighting my way through a wild river rapid to its peaceful end. Because ultimately, the river does what it wants. And I have to enjoy the river on its own terms.

I get out at Fort Spring to eat. I’m two miles from the campground, and two rocky rapids as it turns out. I go around two bends and hear a loud roar ahead. Most of these rapids are small enough for me to eyeball a line, but this one doesn’t have a clear channel from the top. The main channel in the middle goes right into a rock at the bottom. Dammit, I have to get out.

I scout from the left. Sure enough, the center line would be fine if that rock wasn’t waiting to smack into my boat. The far left line right in front of me looks more promising. It’s tight, but I can get it with a quick right turn. I get back in and run through it as planned, but not without scraping the bottom. Good thing my packraft is made for that kind of abuse. I’ve hit rocks with it so many times and have yet to rip a single hole anywhere.

I get to another rapid and try to scout from the top. The current is too fast and I have to improvise. I go for the biggest channel I can find and get stuck on top of a rock just under the current.

Shit! Water is rushing around me on both sides. I lean out and put my paddle in the current, well aware that I don’t want to fall out and chase my raft down this bony ass rapid. Soon I’m freed and go out on the current backwards. I spin around and charge out on the tailwaves, staying clear of more rocks on the right.

This had better be it. Without a doubt, rapids like those are easier at high volume, even if it means bigger waves and higher whitewater grade. But today the river level is rated “Lower Runnable”, requiring more technical lines around the rocks.

I shore in at the campground and set up camp close to the river. When I go to the office to check in my site, I hear the meow of a kitten from behind the front desk. The lady tells me that it hitched a ride with her to work today. Apparently, the cat climbed through the engine of her car and sat just under the hood that morning. She got in the car and drove to the campground, and when she got out, she heard it meowing from under the hood. When she opened the hood to look, there it was. Not a scratch. Somebody has a guardian angel.

That night, a thunderstorm passes over the valley. I barely notice as the downpour bombards the rainfly on my tent.

Day 7: Take Me Home

The depot in Alderson is five miles away. The river, according to the campground website, has more rapids like the ones from yesterday. I’m reluctant to paddle any further. The last thing I want is to fall out in some bony rapid and hit my leg on a rock. Instead, I pack up and hike on the road.

Stuarts Smokehouse is well known on the river, very largely because they have signs that say things like “Pulled Pork & Brisket at Stuarts, 5 Miles!” I make a strategic three mile hike to get there at 11 when they open for beers and a brisket dinner. Outside, the sign reads “Cold food, warm beer, ugly women.” Sold!

I reach Alderson and wait out the afternoon at the train depot. Several boring hours later, I board the train one last time with my river gear in my backpack.

Later, the golden sun lights the fog gathering at the top of the New River Gorge as #51 passes under the high bridge and out of the canyon. It has a trail system and river of its own – also accessible by the Amtrak Cardinal.